Following the Money 2015: How the 50 States Rate in Providing Online Access to Government Spending Data

Every year, state governments spend hundreds of billions of dollars through contracts for goods and services, subsidies to encourage economic development, and other expenditures. Accountability and public scrutiny are necessary to ensure that the public can trust that state funds are spent as well as possible.

Downloads

Executive Summary

Every year, state governments spend hundreds of billions of dollars through contracts for goods and services, subsidies to encourage economic development, and other expenditures. Accountability and public scrutiny are necessary to ensure that the public can trust that state funds are spent as well as possible.

In recent years, state governments across the country have created transparency websites that provide checkbook-level information on government spending – meaning that users can view the payments made to individual companies as well as details about the goods or services purchased or other public benefits obtained. These websites allow residents and watchdog groups to ensure that taxpayers can see how public dollars are spent.

In 2015, all 50 states operated websites to make information on state expenditures accessible to the public and these web portals continue to improve. For instance, in 2015, all but two states allow users to search the online checkbook by agency, keyword and/or vendor, and 44 states provide checkbook-level data for one or more economic development subsidy programs. Many states are also disclosing new information and are making it easier for outside researchers to download and analyze large datasets about government spending.

This report, our sixth annual evaluation of state transparency websites, finds that states continue to make progress toward comprehensive, one-stop, one-click transparency and accountability for state government spending. Over the past year, many states have launched new and improved websites to better open the books on public spending, or have adopted new practices to further expand citizens’ access to critical spending information. Some states, however, still have a long way to go.

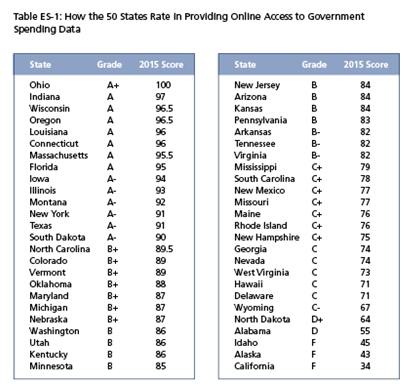

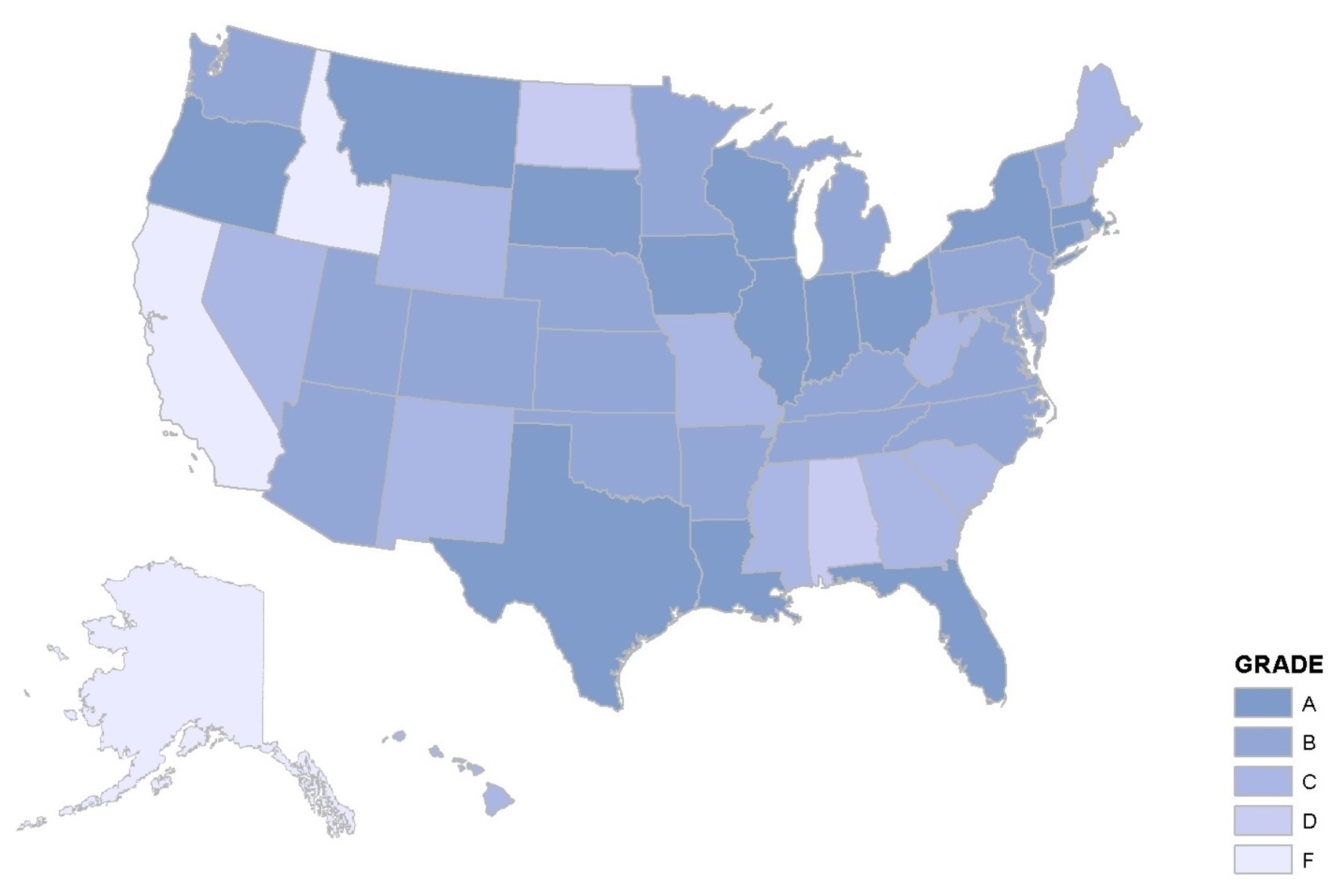

Figure ES-1: How the 50 States Rate in Providing Online Access to Government Spending Data

Over the past year, several states have launched new websites or made substantive upgrades to their existing websites.

- Colorado re-launched its transparency portal with a new, more user-friendly data viewer.

- Kansas’ website overhaul included the addition of keyword search functions, downloadable data and a page that details the information excluded from the website.

- Massachusetts significantly increased the number of quasi-public agencies accounted for via the state’s transparency website.

- Montana continued to improve on its provision of information pertaining to economic development subsidies.

- Nevada made a tax expenditure report available for the first time, as well as data on three of the state’s five most important subsidy programs.

- North Dakota improved its website with partially downloadable data.

- Ohio unveiled an entirely new transparency website incorporating all of the features typically found on leading sites, as well as cutting-edge functionality.

States have made varying levels of progress toward improved online spending transparency. (See Figure ES-1 and Table ES-1.)

- Leading States (“A” range): Fourteen states lead in online spending transparency, representing an all-time high in this category. They have created user-friendly websites that provide visitors with accessible information on an array of expenditures. Not only can ordinary citizens find information on specific vendor payments through easy-to-use search features, but experts and watchdog groups can also download and analyze the entire checkbook dataset.

- Advancing States (“B” range): Eighteen states are advancing in online spending transparency, with spending information that is easy to access but more limited than Leading States. Most Advancing States have checkbooks that are searchable by recipient, keyword and agency.

- Middling States (“C” range): Thirteen states are middling in online spending transparency, with comprehensive and easy-to-access checkbook-level spending information but limited information on subsidies or other “off-budget” expenditures.

- Lagging States (“D” range): The two Lagging States fail to provide tax expenditure reports and provide almost no checkbook-level detail on the recipients of economic development subsidies (North Dakota makes data available for a single program). There are significantly fewer Lagging States this year than last, evidence of states’ ongoing progress in opening the books on spending.

- Failing States (“F” range): Three states fail to meet several of the standards of online spending transparency. For example, two of the three do not host an online database for searching or viewing expenditure details, and only one makes tax expenditure reports available via a central transparency portal. None of the Failing States provide any information on economic development subsidies.

Some states are innovating new features for online transparency. They have developed new protocols and datasets and introduced new website functionality, giving the public unprecedented ability to monitor and influence how their government allocates resources. For instance:

- Ohio’s site populates instant search suggestions based on the letters typed into the search bar, creating a website that looks and behaves much like the top search engines Ohioans most commonly visit and interact with elsewhere on the internet. This feature aids transparency by helping users track down information without needing prior knowledge of exact search terms. In addition, every web page has the phone number and email address for a point of contact in state government, as well as social media “share” buttons.

- Minnesota, Oklahoma and Texas have added new detail, and made data easier to understand, with new visualization tools including maps, graphs and a taxpayer “receipt” that explains how a citizen’s tax dollar is distributed to different state spending functions.

- Florida now posts the value of payments excluded from the checkbook for confidentiality reasons, enabling users to better grasp the missing state payments that policies prohibit from being listed in the checkbook database.

All states, including Leading States, have opportunities to improve their transparency.

- The checkbooks in five states have limited searchability.

- Only eight states provide checkbook-level information that includes the recipients of each of the state’s most important subsidy programs. While many other states provide checkbook-level information for some of their major subsidy programs, disclosure for all programs would provide greater transparency and accountability.

- Six states do not provide tax expenditure reports that detail the impact on the state budget of targeted tax credits, exemptions or deductions.

- In addition to improving the comprehensiveness of their transparency portals, states should begin to enhance user-friendliness in design and functionality.

- No state provides a comprehensive list of government entities outside the standard state budget. Ideally, all governmental and quasi-governmental entities – even those that are entirely financially self-supporting – would integrate their expenditures into the online checkbook, and a central registry of all such entities would be available for public reference.

- Even top-scoring states should continue to expand the universe of data accounted for by their transparency portals. Important advancements would include detailing all active public-private partnerships, and supporting municipal and county level transparency and making those data available centrally.